There are two reasons to try grass-fed flour Kernza in your next sourdough bread. First, it gives the bread a unique flavor profile that some bakers call savory or herbal—and most eaters call savory. The second reason is because Kernza flour has the potential to dramatically improve the environment.

What is Kernza?

Almost all of the world's major food crops, including wheat, rice, corn, oats, rye, barley, sorghum, sorghum, and sugarcane they are herbs. Although there are more than 10,000 species of grasses, their potential as food stems from their ability to produce large, nutritious seeds. We consumers call those seeds grains, which we eat for their carbohydrates, proteins and essential minerals. Kernza (also called intermediate wheat grass,Thinopyrum intermedium) is a distant relative of wheat that produces seed heads that are similar to wheat. It is native to grasslands in Europe and Asia.

Why add another to the long list of grains eaten by the human population? Because all the world's grains are annuals, which means that every year farmers have to till the soil and plant fresh seeds. Kernza, the trademarked name of the intermediate wheat grass, is perennial, meaning (in theory, at least) it can be planted once and harvested repeatedly, year after year.

Environmental Advantages of Kernza

Whenever a field is cleared of vegetation with its soil turned in preparation for planting, the bare soil is exposed to the elements. Wind can blow irreplaceable topsoil off the field (think: Dust Bowl 1930s) or rain erodes soil, robbing it from fields and depositing it in rivers and streams. If perennial crops such as Kernza can be developed, keeping the ground covered throughout the year, plowing can be eliminated and precious soil can be protected and conserved.

The mission of Earth Institute in Salina, Kansas is the development of perennial cereal crops like Kernza. When I visited the Land Institute in the early 1990s, the first thing their director at the time, Wes Jackson, did was take me to a river that runs along their farm. The river was the color of milk chocolate, carrying topsoil from Midwestern farms to the Mississippi Delta. “That's why,” Wes said, pointing to the river, “we're doing what we're doing.”

A second problem with plowing is caused by the amount of fuel needed to power a tractor each time it moves across a field. Very few tractors, especially large models that pull plows across hundreds of acres of land, get the kind of fuel-efficient mileage of, say, a Prius. Tractors generate a lot of carbon dioxide, a gas that warms the climate.

Another danger of plowing—and this is a subtle but critical one (something I learned as a PhD student in Earth Science, but not the kind that often gets written on the front page of a newspaper)—is that plowing exposes tiny particles of soil organic matter to microscopic organisms. Bacteria and fungi pass on nutrients previously hidden by them in distant cracks in the soil. Once consumed, that soil organic matter, rich in carbon and useful in all sorts of ways to plants, is no longer available to enrich the soil.

Worse still, the loss of soil organic matter means that the carbon once stored in the soil is transferred to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, waste product of microbial decomposition. Move carbon dioxide from the ground into the atmosphere and the planet continues to get hotter.

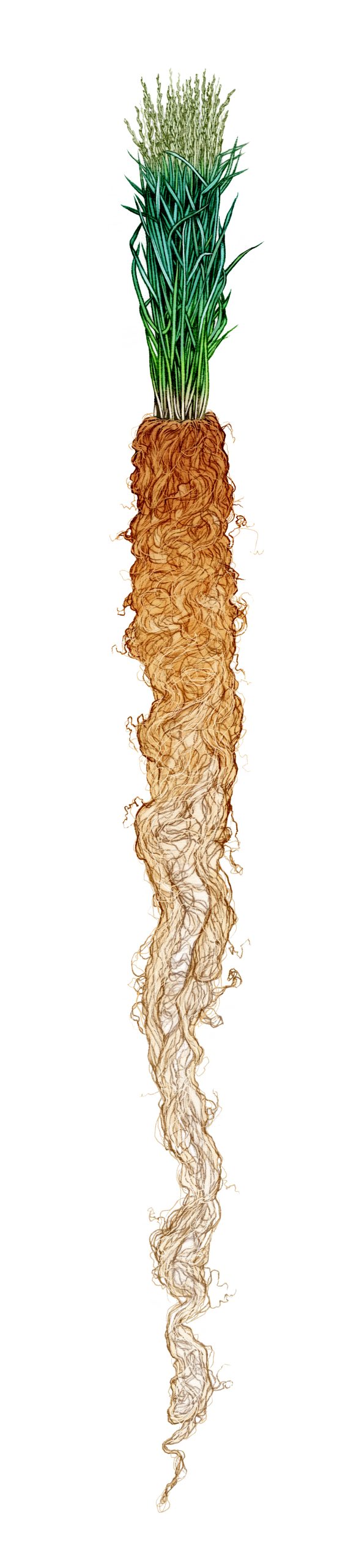

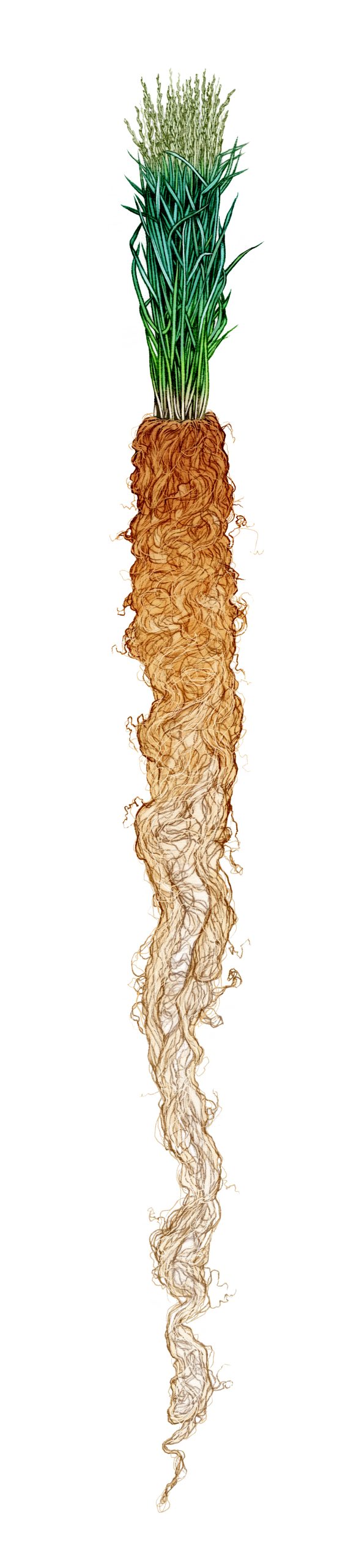

Unlike annual corn, soybeans and wheat, perennial Kernza does not need to be planted every year. Instead, it continues to grow from the same base and much of the plowing can be avoided. Furthermore, when compared to wheat, Kernza has an exceptionally deep and abundant root system. Kernza actually transfers carbon dioxide from the atmosphere deep below the earth's surface, reversing carbon emissions and effectively delaying climate change. That alone is cause for celebration.

Add it all together and you have a crop that sequesters atmospheric carbon, keeps the soil covered year-round, protects the soil surface from erosion by wind and rain, and reduces the number of passes required for farm equipment.

There's an added benefit for us bakers: kernza flour makes delicious bread.

Kernza breeding challenges

With the goal of creating, virtually from scratch, a plant capable of producing extraordinary amounts of grain without the need to replant each year, researchers at the Land Institute began a breeding program in 2003. Among their early objectives was to select plants with large seeds and abundant seeds: the more each plant produces, the greater the yield of harvested food grown on each hectare. It is not as easy as it sounds. By comparison, grasses already in the human pantheon (wheat, corn, rice, etc.) have been selected by farmers year after year for their ideal traits since the dawn of human settlement roughly 10,000 years ago. This is a great start.

Plant breeders, ancient or modern, you must save the seeds of plants (and not eat them) with the best combination of attributes. These are many, among them: yield, resistance to pests, deep roots, ability to produce grain year after year, resilience to climate, resistance to breaking when seeds are shaken from the stem, ability to grind freely, large seed size and strong stem. don't blow lightly on windy days.

When, at the end of a growing season, a field trial exhibits one or two beneficial traits—say, large grains and an improved yield—it should be crossed with the winners of the climate-resistant strain and replanted. There is no guarantee that the crossbred varieties will excel either in the original traits or in the newly hoped for match. And if it does this year, it might not be next year, when the weather is a little drier or a little warmer. Successful plant breeding, even with the tools of modern science, takes decades. (Faster, it is hoped, than the 10,000 years it took for existing cultures to develop, but still many years.)

While promising, Kernza is not a perfect crop. So far, Kernza's yields on a per hectare basis are only about a quarter of those derived from a similar field of wheat. More discouragingly, its yields decline rapidly in the second or third year after planting, although the remaining grass makes excellent animal forage. Consequently, it should probably be replanted every three to five years. Not yet what breeders hope for, but still better than plowing and planting every year.

The Land Institute has collaborated with researchers around the world in France, New Zealand, Sweden, Israel, Turkey, Russia, Germany, Denmark and across the United States.

Early returns are positive. Farmers are interested in experimenting with new culture; and Kernza's ability to rapidly sequesters carbon and keep extra carbon in the soil in long-term sequestration means it is absolutely worth additional study.

Baking Bread with Kernza

Getting Kernza to grow profitably is only one piece of the puzzle of bringing it to market at scale. Farmers will only grow thousands of hectares of Kernza if they can make a profit. Without the economies of scale accrued by farmers and millers accustomed to managing thousands of acres and tons of grain, the price for Kernza remains extremely high.

For bakers who may use Kernza flour there is a learning curve. As is the case with flours made from ingredients other than wheat, Kernza flour behaves differently from what wheat-based bakers are familiar with. Not only is its protein content higher than most baking flours, but its gluten structure, according to at least a report, is somewhat inelastic and viscous. Like all grains, there are other uses for Kernza beyond bread, including cereal, whole grains, and sprouted grain crackers. It can also be malted for use in whiskey, beer, and cakes and biscuits usually made with softer wheat.

Because Kernza seeds are smaller than those of wheat, the flour produced from Kernza tends to be higher in bran content and may therefore require more water to hydrate. However, early adopters respond positively to Kernza's flavor profile: “nutty” is the most cited term I see; although “cinnamon,” “herbal,” and “sweet” also appear as descriptors. According to the Land Institute, bakers also seem to appreciate being at the forefront of a baking challenge that is contributing to the fight against climate change.

Nutritionally, Kernza is higher in protein, fiber, carotenoids and other antioxidants, when compared to wheat flour. Its protein content is twice that of white wheat berries. Compared to whole white wheat, it contains almost five times more calcium and nearly twice the amount of dietary fiber (almost seven times more fiber than found in all-purpose white flour).1.

Where to find Kernza flour

In order for Kernza to be fully included in the commercial food system, several links in the commodity chain must be strengthened. Farmers must produce grain with consistency; millers who are able to work with small parcels should be located near the farms that grow Kernza, (hundreds or thousands of pounds, instead of the millions of pounds that usually go through large rolls in industrial mills); and professional bakers must be comfortable working with a product that is likely to be much less consistent in its performance than the blended flours they are used to.

All that said, home bakers should consider experimenting with Kernza. If you want to try Kernza, include some actual sellers Prairie Foundation (look under the Provisions tab), Breadtopia, which sells whole grainsand the Earth Institute has licensed these DISTRIBUTER.

Kernza FAQ

Is Kernza gluten free?

Kernza is similar to annual wheat and, therefore, is not gluten-free.

What does Kernza taste like?

Kernza has a slightly sweet, herbaceous and nutty flavor profile.

Is Kernza whole grain?

If you grind Kernza at home, it can be used as a whole grain flour added to breads, pancakes, waffles and more. When buying Kernza flour, make sure it is unsifted if you want it whole grain.

What is expected next?

Look Perfect Loaf's Kernza Sourdough Bread Recipewhich uses 30% freshly ground Kernza for a healthy and delicious bread.